Notions

My Aunt Jean was a collector. Right after her husband, Steve, passed in 2016, I went to Mechanicsburg, PA to filter through her house with her. We spent hours together, packing and unpacking, while I listened to her muse on the objects she held dear, the things she would have the hardest time parting with when she moved out of her home.

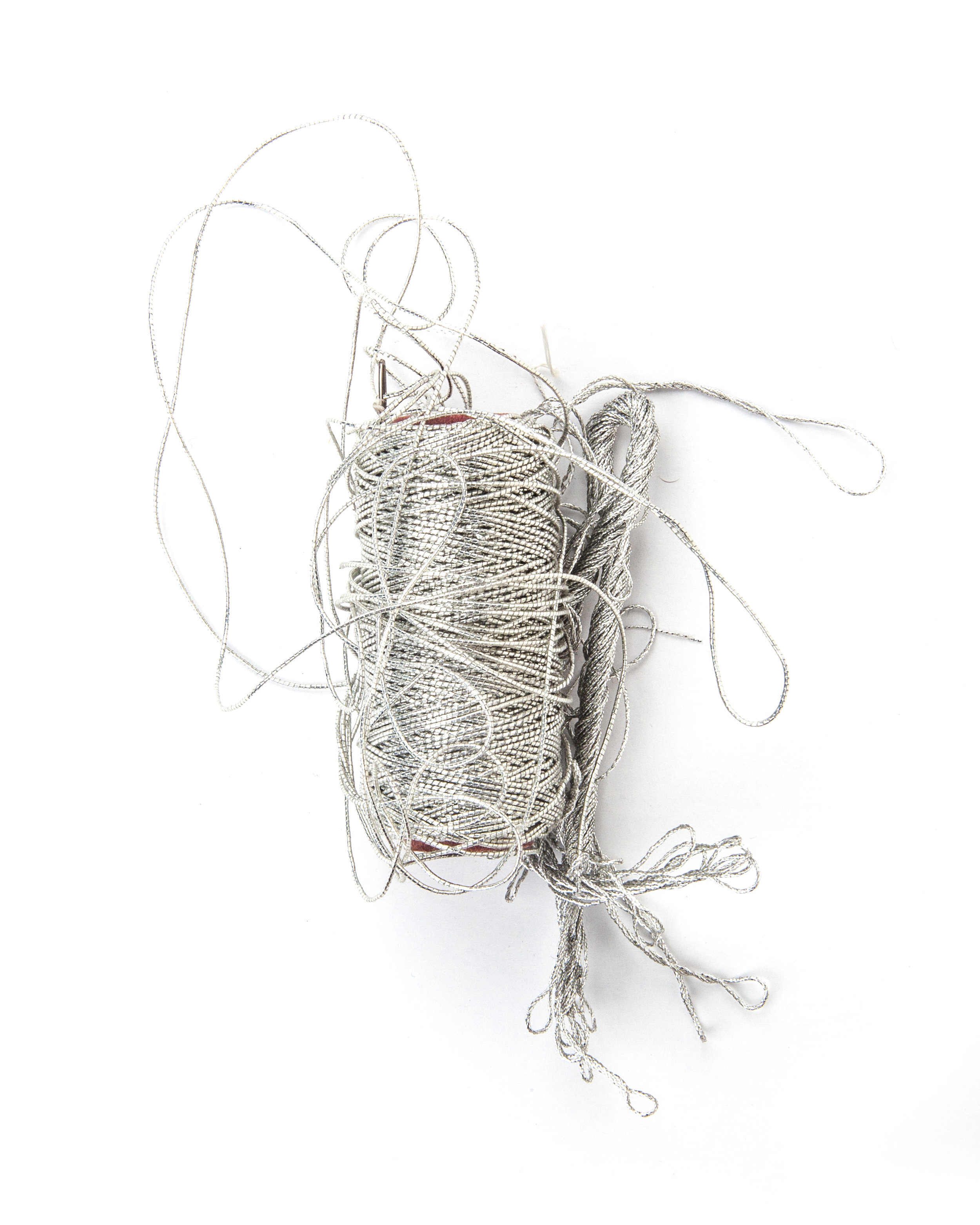

Jean’s collections were not meticulous but were arranged in an order which made sense to her. During that time together she gave me a sewing box filled with notions, thread, spare buttons, among other objects of hers she rightfully assumed I would appreciate. In February 2019, at 85 years old, Jean passed suddenly due to complications from Parkinson’s. I had visited her recently, and had made photographs of her and her things over the years, but had yet to touch the sewing box. My investigation of this box began then, as have many of my photographic explorations, with examining the “original order” (the organization and sequence of records established by the creator of its contents) and photographing a “description” of her collection (the process of creating access tools that allow individuals to browse a surrogate of the collection to facilitate access by creating a record of the collection).

Identity is tied to what we surround ourselves with and how we occupy space. When we consider the “original order” of ourselves, we are able to dig into what makes us us, and how we have been influenced by our cultural landscape. For instance, Jean was raised in the fallout of the Depression, and her commodity-minded habit of keeping things which may be useful someday is demonstrated in this collection. She was a feminist, wildly ahead of her time, had a PhD in Public Administration, and in a generation of women who often tempered themselves, she never allowed herself to be seen as “the woman behind the man.” In fact, when she accepted a job as Library Director at Union College in Schenectady, NY, her husband followed her there, and The Schenectady Gazette determined that “Man Follows Woman to Job” was the most interesting line to take in announcing her appointment. She was an activist, and lived (and protested) in New York and DC during the height of second-wave feminism.

We have inherited identities bound to dominant paradigms and factors beyond our control. These factors, such as the entities which disperse facts and record histories, are filtered by colonialism, adjudicated by white supremacy, and controlled by a patriarchal structure which precedes us and will likely remain long after we are gone. Our hierarchical place in these systems is constrained by our geographic location and our access to resources as base as clean water and as privileged as advanced education. There are alternate narratives of course, but the prevailing narrative is drawn directly from biased sources.

With this work, I am interested in the recognizable nostalgia of domestic sewing notions as symbols of “homemaker” femininity, and how the the context of feminism has changed in my aunt’s eight decade lifetime. She was able to mother, keep house, sew, clean, and pursue advanced degrees, all while working full time. The last line of her obituary (written by her son) read: “On February 16, 2019, Jean died at home, likely a little disappointed in the progress we made in her lifetime. She had great expectations for humanity.”

I am digging into the space between history and our story, trying to excavate the building blocks of this broken and flawed systemically oppressive cultural moment to see if we can rebuild with softness and vigor, as femmes in power, rather than submitting to the notion that femininity does not equal power.

(1) https://www2.archivists.org/glossary/terms/o/original-order

(2) https://www2.archivists.org/glossary/terms/d/description